As Congress raced against the clock last week to pass the $1.7 trillion omnibus spending bill, all eyes were on the bigger issues: things like avoiding a government shutdown, funding for Ukraine, and spending increases for clean energy and the environment. But tucked quietly into the bill were two items that will prove to be a VERY big deal for both pregnant people and nursing parents in the workplace.

These items are the The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA) and The Providing Urgent Maternal Protections (PUMP) for Nursing Mothers Act, and their passing means new rights for working parents (and parents-to-be). Surprisingly, both measures were met with sweeping support from both Democrats and Republicans. We love a good “getting along” moment, especially when it comes to policies that will make it easier to maintain the balance between parent and professional.

Let’s break these provisions down and see what they’re all about, shall we?

The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act

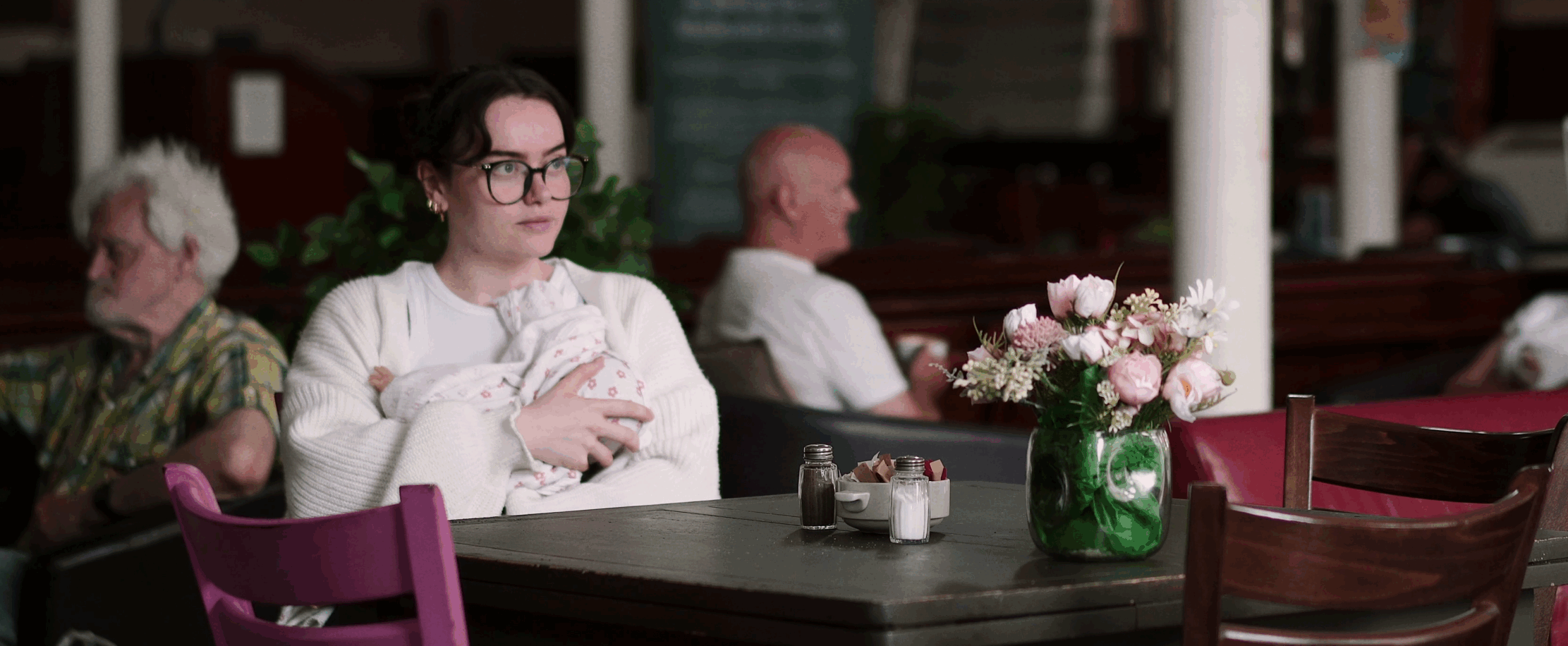

Anyone who has ever been pregnant and employed at the same time knows that incubating a whole entire human can require a few workplace concessions. You need time off for doctor’s appointments, parental leave, and everything else being a pregnant employee entails. But though Congress outlawed pregnancy discrimination in 1978, pregnant workers still often find themselves denied reasonable accommodations when it comes to pregnancy-related issues — like more frequent breaks, for example, or schedule changes to facilitate appointments (or things like morning sickness).

Even worse, pregnant workers in some industries have not been allowed to alter their usual duties which can be potentially hazardous to expectant parents, like lifting heavy objects, working with chemicals, or entering into dangerous situations as, say, a first responder. No one should ever be forced to choose between their job and the safety and wellbeing of their baby-to-be, but it happens far too often.

“Women now comprise half the workforce, and roughly 85 percent of working women will be pregnant at least once,” says the ACLU. “Census figures show that most workers can and will remain on the job well into their final month of pregnancy. Simply put, pregnancy is a normal condition of employment — and employers should be obligated to treat it that way.”

Enter the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act. This bipartisan act extends the protections that pregnant employees need to ensure that they can keep working safely and comfortably (and in turn, maintain their earning power) throughout the duration of their pregnancy. The PWFA requires all employers to provide the reasonable accommodations that pregnant employees need. It’s modeled after the Americans With Disabilities Act, which states that employers must make the same reasonable accommodations for disabled workers — but since pregnancy is not considered a disability, pregnant workers were not protected under that act, hence the need for a new one.

So if a pregnant worker is suffering from an incapacitating bout of morning sickness and temporarily needs to adjust hours, for example, or requests that a non-pregnant employee take over a certain duty that could be hazardous, the rights to do so will be upheld by the PWFA.

“Pregnant workers were falling through the cracks with our existing laws,” Dina Bakst, co-founder of A Better Balance, an advocacy group that aided in drafting the bill, told The Washington Post. “This is an incredible milestone for gender, racial, and economic justice.”

The PWFA also protects against companies discriminating against job applicants, or denying them employment, on the basis of pregnancy. Win!

Enter the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act. This bipartisan act extends the protections that pregnant employees need to ensure that they can keep working safely and comfortably (and in turn, maintain their earning power) throughout the duration of their pregnancy. The PWFA requires all employers to provide the reasonable accommodations that pregnant employees need. It’s modeled after the Americans With Disabilities Act, which states that employers must make the same reasonable accommodations for disabled workers — but since pregnancy is not considered a disability, pregnant workers were not protected under that act, hence the need for a new one.

So if a pregnant worker is suffering from an incapacitating bout of morning sickness and temporarily needs to adjust hours, for example, or requests that a non-pregnant employee take over a certain duty that could be hazardous, the rights to do so will be upheld by the PWFA.

“Pregnant workers were falling through the cracks with our existing laws,” Dina Bakst, co-founder of A Better Balance, an advocacy group that aided in drafting the bill, told The Washington Post. “This is an incredible milestone for gender, racial, and economic justice.”

The PWFA also protects against companies discriminating against job applicants, or denying them employment, on the basis of pregnancy. Win!

The Providing Urgent Maternal Protections (PUMP) for Nursing Mothers Act

Pumping at work (literally) sucks — and when you don’t have an optimal environment in which to do it, it’s even worse. Inadequate pumping spaces, a workload that doesn’t always accommodate pump breaks, anxiety over privacy, a boss that treats you downright disdainfully for pumping in the first place … the list goes on.

According to the Office on Women’s Health, more than 80% of new mothers in the United States begin breastfeeding, and 6 in every 10 new mothers are in the workforce — which basically means that there are a whole lotta nursing parents dealing with the hassles that come with pumping at work.

Though the Break Time for Nursing Mothers law was passed in 2010, which stated that employers must provide reasonable break times and private (non-bathroom) spaces for employees to pump at work, this has proven inadequate for many; according to the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee, “nearly one in four women of childbearing age are not covered by the Break Time law.” This included many salaried workers and employees in non-hourly positions, like nurses or teachers. The 2010 law may have laid the important groundwork, but still left much to be desired.

With the passing of the Providing Urgent Maternal Protections for Nursing Mothers Act (PUMP), the protections set in place by the Break Time law are strengthened. While the Break Time law covered hourly employees for up to a year, PUMP extends those protections to both salaried and hourly employees for up to two years — which, according to the ACLU, will covered approximately an additional 9 million breastfeeding workers.

The PUMP act not only covers more breastfeeding employees, but also requires that employers provide ample time and space to pump, and mandates that time spent pumping must also count as hours worked if an employee is doing their job at the same time. “The PUMP for Nursing Mothers Act clarifies that although the breaks taken under the law are typically unpaid, if hourly workers are not actually relieved from duty while pumping, then that time should be counted as hours worked,” explains the ACLU.

The PUMP act not only covers more breastfeeding employees, but also requires that employers provide ample time and space to pump

This article was first published here. You can read the original article in full here.